Abstract

Background. Sickle cell disease is a risk factor for stroke. Findings from previous studies examining an association between sickle trait and stroke have been conflicting (Roach ES, 2005; Caughey MC, et al, 2014).An estimated two million people in the United States (U.S.) carry sickle trait (Key NS, et al, 2015). Carrier prevalence among African American newborns is 7-8% and up to 4% among Caribbean Hispanics, especially among people from the Dominican Republic and certain other nationalities (Lorey FW, et al, 1996; Siddiqui S, et al, 2012). Trait carriers are at increased risk of renal papillary necrosis, chronic kidney disease and thrombosis (Naik RP, et al, Bucknor MD, et al, 2014; Porter B, et, 2014). We hypothesized that cohorts of high-risk elderly populations who carry sickle trait may provide an opportunity to examine the question of cerebrovascular risk within the context of other associated risk factors.

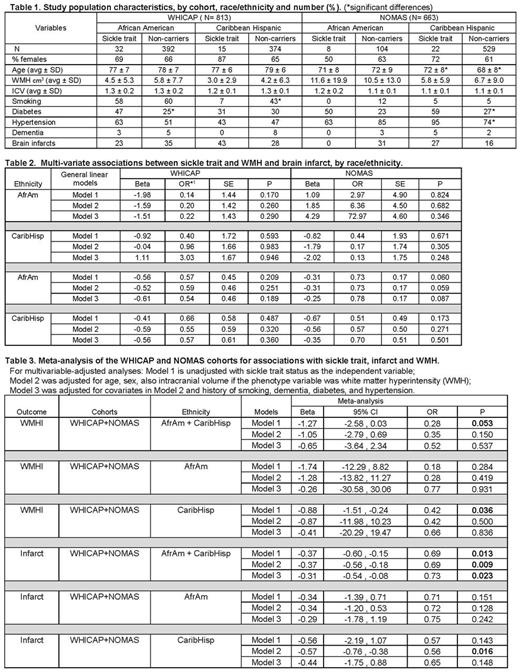

Methods. We examined cross-sectional associations between sickle trait and MRI-defined cerebral infarct and small vessel abnormalities, defined by a quantitative trait of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), in 1476 participants from two well-phenotyped, high-risk elderly population-based cohorts, the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP) (Brickman AM, et, 2008 and 2010) and the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS) (Monteith T, et al, 2014). Participants shared by the cohorts were eliminated from WHICAP data. All 536 African American and 940 Caribbean Hispanic participants in the combined cohorts were genotyped for sickle trait. MRI protocols and WMH phenotyping used in both cohorts were performed as previously described using a 1.5T scanner and common pathologically-informed algorithms with good intra-reader reliability (Brickman AM, 2008; Verhaaren BF, 2015; Gutierrez J, et al, 2015). Univariate and multivariable-adjusted analyses were performed with statistical software packages SAS, SPSS and R. Beta coefficients from the linear regression models (WMH as the outcome variable) were exponentiated for interpretation as odds ratios.

Results. Prevalence of sickle trait within each race/ethnic group was comparable across the two cohorts: 8% and 7% among African-Americans in WHICAP and NOMAS, respectively, and 4% in both cohorts among Caribbean-Hispanics, primarily Dominicans. Based on trait prevalence among each racial/ethnic group by newborn screening within the same geographic region, overall standardized mortality ratio was 0.96 (CI 0.76-1.20). Modestly significant negative association was found between sickle trait and WMH in the trans-ethnic sex and age adjusted meta-analysis (β=-1.27, OR=0.28, p=0.053) across both cohorts, primarily driven by Caribbean-Hispanics (β=-0.88, OR=0.42, p=0.036). The strongest significant association in the trans-ethnic sex and age adjusted meta-analysis was found between sickle trait and infarct (β=-0.33, OR=0.72, p=0.009).

Conclusions. In contrast to studies that included clinically-defined stroke among younger African-Americans, our findings in a meta-analysis of two race/ethnically diverse elderly cohorts suggest a modest negative association between sickle trait and WMH, a marker of small vessel abnormalities, and a consistent significant negative association for infarcts. Results were driven largely by the Caribbean-Hispanic groups. Sample size limited study power and may have overestimated associations. NOMAS subjects were younger and had fewer infarcts than in WHICAP. Additional limitations were differences in prevalence by trait status of known vascular risks in one or both cohorts, although these factors were differentially distributed between carrier and non-carrier. Prevalence of sickle trait among each of these elderly racial/ethnic groups supports existing data that trait does not affect lifespan (Castro O, et al, 1987). Overall, our findings suggest that sickle trait may confer a modestly lower risk of two types of MRI-defined cerebrovascular pathology in a multi-ethnic, high-risk elderly sample. Confirmation and exploration of potential mechanism(s) requires larger sample sizes with MRI-defined phenotypes, as concurrent risk factors and racial/ethnic differences may affect the association.

Acknowledgments Support was provided by NIH PO1AG07232, R01AG037212, RF1AG054023 (WHICAP), 6R01 NS029993(NOMAS), R01 AG034189 and R56 AG034189

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal